Mouth Care Matters in Older People

Our population is ageing as the health care workforce is ever more stretched; is mouth care being sacrificed on the altar of busyness?

The scale of the problem

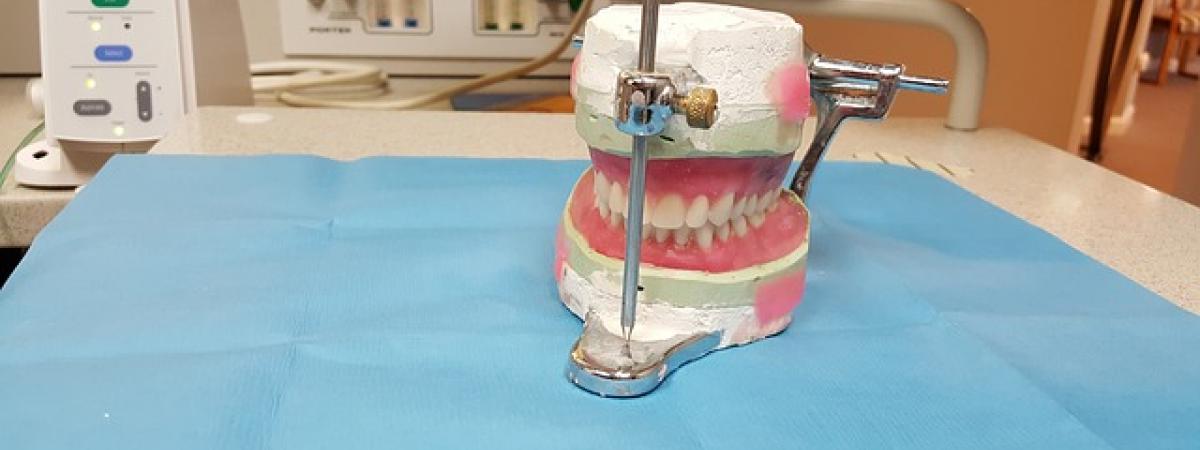

Health journalist Mary Otto describes a “silent epidemic” of oral disease in her book entitled “Teeth”. Rotting stumps, food caked between stained, cracked and loosened teeth and ill-fitting dentures coated with the morning’s Weetabix are a depressingly familiar sight amongst our older people in care; thrush thrives when your oral microbiome is out of balance through poor dental hygiene, with up to 10% of older people being affected. 50-70% of denture wearers are predisposed to oral candida infection.

Public Health England estimate that there will be 14 million people aged 65 and over by 2032 (up from 11 million in 2015). The proportion of adults in England who have no remaining natural teeth (who are “edentate”) has fallen from 28% in 1978 to 6% in 2009. That’s a lot of teeth to clean.

For those many older people unable to clean their own teeth, mouth care should be an essential nursing responsibility but it can, sadly, be treated like an optional extra, says Eileen Shepherd, clinical editor of the Nursing Times, and that’s when dental decay sets in. When residents are wheeled to breakfast without their dentures, it’s a sign that mouth care has been missed again.

The root cause of many diseases

According to the Oral Health Foundation “what’s going on inside our mouth can be a very useful indicator for the state of our overall health”. I’ve nursed people with brain abscess, endocarditis and pneumonia originating in infections of the teeth; in cardiac surgery I would watch doctors examining patients’ mouths before their hearts.

What’s going on inside our mouth can be a very useful indicator for the state of our overall health.

Malnutrition, meanwhile, is a particular problem among the elderly, with 1.3 million of the 3 million people affected in the UK over the age of 65. Having a mouthful of plaque, tartar, caries and inflammation will hardly help the appetite, whilst poorly fitting dentures can make it hard to chew. If you’re on a pureed diet, thickened fluids or medicines that dry the mouth, then having a clean mouth becomes a particular challenge.

Self-esteem can plummet in people with poor dental hygiene. It’s hard to smile when you’ve got bad teeth; decent dentition can bestow a sense of dignity on a frail older person already battling the other losses of old age including continence, memory and mobility.

Prevention is paramount

Sometimes residents with dementia resist oral care, becoming confused or agitated by the invasive procedure. For this, there is no simple solution, and more heart-breaking still is when the resident refuses to open their mouth for food and drink too.

Other barriers to oral care are easier to address and include a lack of training, mouth care assessment tools, policies and equipment, as summarised in the Mouth Care Matters Campaign, launched by Health Education England in 2015.

The “relentless staff shortage in the care home sector”, as reported by the King’s Fund, is also relevant. With 4 in 10 care home workers leaving their role every year, an inadequate workforce represents one of the biggest challenges to oral health. Carers can be too busy to consider mouth care – or act as escorts for essential visits to the dentist. Community dental services meanwhile are rare, with one care home manager calling on the Health and Social Care Secretary to arrange for increased dentist visits to care homes.

“The teeth keep a record of our lives, locked in their enamel. They identify us even beyond the grave,” says Mary Otto. What stories do the teeth of our older people tell about the care they are receiving?