Surprising facts about your spleen

published in Reader's Digest,

05 April 2017

Compared to the heart, the brain and the liver, the spleen is not viewed with much esteem. Yet this ‘organ of mystery’ has featured throughout history and is much referred to in literature, art, sport and medicine.

The Spleen in History

During the time of the Roman Empire, a prominent Greek physician called Galen put forward the now-debunked idea that human health and disease could be explained by the balance or imbalance of four bodily fluids: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. The spleen was said to produce black bile.

As well as affecting your physical health, over- or underproduction of black bile by the spleen was thought to affect your mood, resulting in anger and, curiously, laughter. Proving that even great minds can believe such medical myths William Harvey (1578-1657), the famous doctor who discovered the circulation of the blood, said that “the spleen causes one to laugh”.

That a sick spleen could underlie physical and mental health problems was an attractive idea: it would make for easy medicine. Sadly, it’s not that straightforward, and these theories are consigned to history, superseded by better science.

The Spleen in Literature

English is a difficult language to learn, partly because we use some pretty baffling expressions. Just as we ‘pay through the nose’, ‘jump out of our skin’ and ‘put our foot in our mouth’, we also ‘vent our spleen’ when forcefully expressing our anger: again referring to the idea that the spleen contained black bile, a source of irritability and rage.

In the poem ‘Maud’ by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the spleen is referred to three times; Shakespeare talks of Tybalt’s ‘unruly spleen’ as a possible factor in the murder of Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet.

In the poem ‘Maud’ by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the spleen is referred to three times.

The Spleen in Sport

Evan Murray, a 17 year old New Jersey high school student, died of a lacerated spleen following a tackle in American football. According to David Ralston, Athletic Trainer in Kentucky, “injury to the spleen in football is a known yet very uncommon injury”.

The spleen is situated on the left side of the body just under the ribcage and to the left of the stomach. Approximately 350 litres of blood pass through the adult spleen each day; a hard blow to the left side of the body in sport can break ribs which could rupture the spleen and cause massive internal bleeding. Sports doctors should be trained to spot splenic injuries; athletes should refrain from sport if diagnosed with an enlarged spleen, perhaps due to infection, since this could make it more vulnerable to rupture.

The Spleen in Art

Leonardo da Vinci depicted the spleen in a pen and ink drawing of the abdominal organs; Gaston Vuillier, a 19th century artist, painted a harrowing image entitled ‘Hammering the Spleen’.

Leonardo da Vinci depicted the spleen in a pen and ink drawing of the abdominal organs.

Modern X-rays of the blood vessels in the spleen have even been turned into artwork: one such image is entitled ‘art-tree of the spleen’ and shows the arteries rather resembling the branching pattern of a tree.

‘Body Worlds’ (if you can call it art), the exhibit of plastinated cadavers and body parts (that featured in the remake of Casino Royale), displays an enlarged spleen next to a fatty liver to graphically warn about the dangers of obesity.

The Spleen in Medicine

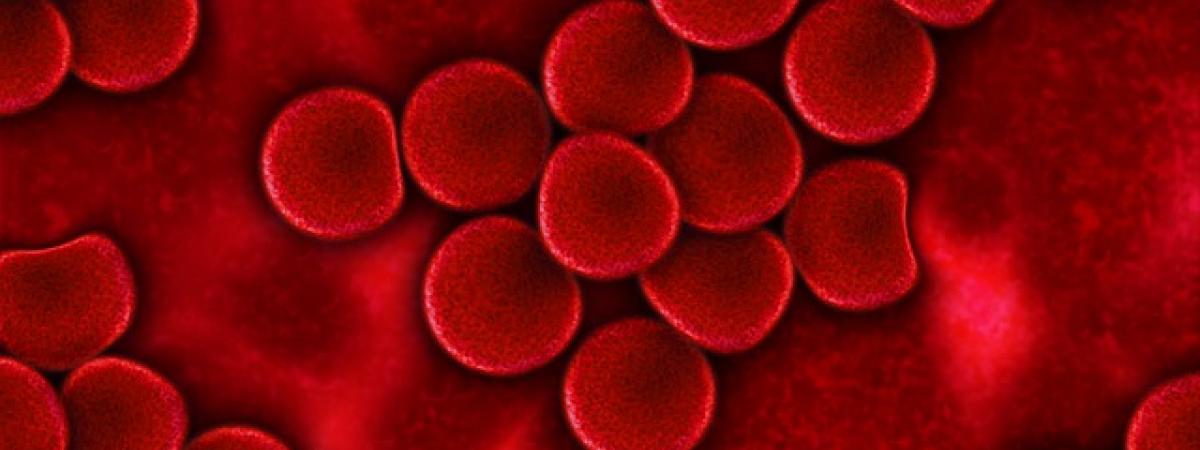

The spleen stands watch over our bloodstream, storing blood platelets (important in blood clotting) and white blood cells (part of the immune system), ready to release into the circulation in the event of a cut or an infection. The spleen is also a very important blood filter, removing bacteria and worn-out and defective red blood cells.

You can live without a spleen: the liver and bone marrow can take over; antibiotics and immunisations can guard against the increased risk of infection. To ‘despleen’ or to be ‘keen to keep the spleen’ is the question in current heart research: after a heart attack, the spleen releases its white blood cells. Whether these cells help or harm the damaged heart is hotly debated in spleen science.